The Atlantic Ocean’s most vital ocean current is showing troubling signs of reaching a disastrous tipping point. Oceanographer Stefan Rahmstorf tells Live Science what the impacts could be.

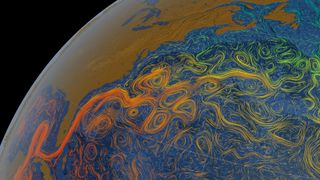

A visualization from space of the Gulf Stream as it unfurls across the North Atlantic Ocean. (Image credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio)

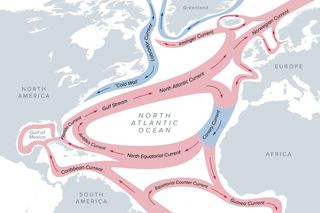

Trouble is brewing in the North Atlantic. Beneath the waves, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which includes the Gulf Stream, acts as a planetary conveyor belt bringing nutrients, oxygen and heat north from tropical waters, while moving colder water south — a balancing act that keeps the Northern Hemisphere warm.

But research into Earth’s climate history shows that the current has switched off in the past, and a growing number of studies suggest that climate change is causing the AMOC to slow, possibly leading it toward a disastrous collapse.

On Monday (Oct. 21), 44 oceanographers from 15 countries published an open letter calling for urgent action in the face of the weakening circulation. They warn that the risk of collapse has been “greatly underestimated” and will have “devastating and irreversible impacts” for the world.

Live Science sat down with the letter’s lead organizer, Stefan Rahmstorf, an oceanographer who runs the Earth system analysis department at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, to discuss the AMOC developments and their potential global effects.

Ben Turner: What role does AMOC play in regulating climates across the Atlantic?

Stefan Rahmstorf: It really plays a very major role. We know this first of all from the paleoclimate record, so the Earth’s history, where the biggest rapid climate changes that we know … are centered around the northern Atlantic region because of the instability of the AMOC.

We also know it from models. Climate models reproduce the AMOC, and you can switch it [AMOC] off by dumping a lot of fresh water into the North Atlantic. Then you get drastic cooling around the northern Atlantic. The strongest signal is near the coast of Norway, where it would get 20 degrees Celsius [36 degrees Fahrenheit] colder compared to if the AMOC was still there.

BT: What’s the evidence for AMOC being a tipping point?

SR: There are abrupt climate changes that you can see in ocean sediments and in Greenland ice core data. There are two types. The first are sudden warming events, so-called Dansgaard-Oeschger events, where during the ice age the AMOC (which stopped south of Iceland) made the jump across towards the north into the Nordic seas where it reaches today. That led to a sudden warming over Greenland, like 10 to 15 degrees Celsius [18 to 27 F] within a decade.

The other type of events are called Heinrich events, when the AMOC shuts down. They’re caused by big ice discharges into the northern Atlantic. You can see ice discharge very clearly in the sediments there, and you can also tell it’s coming from the Labrador Sea area [near Greenland].

That’s another thing that climate models reproduce. We can simulate the last ice age and the Laurentide ice sheet grows steeper and steeper, like a sand hill. Every now and then, there are big ice sliding events that dump a whole iceberg armada into the northern Atlantic. When these icebergs melt, they drop stones at the sea bottom and leave behind a lot of meltwater.

That fresh water is less heavy than the salty ocean water, so it stops the water sinking so deeply and driving the AMOC, causing it to collapse.

BT: The IPCC has estimated the probability of crossing an AMOC tipping point this century as less than 10%. So what led you to raising the alarm with your open letter?

SR: There has been a whole group of studies that were published after the IPCC deadline, so they’re not included in the report, and they have been quite alarming.

These studies look at so-called “early warning signals” in the observational data. When you approach a tipping point, the system starts to wobble back and forth, so there’s more natural variability because the system is less stable — so it’s slower to pull back towards its equilibrium state when it’s just displaced by a little bit of random weather noise, for example.

Those studies have a large uncertainty, but they all point to the tipping point being very likely crossed in this century. Also, we see a lot of reasons why climate models have underestimated the AMOC instability. One image in the latest IPCC report shows how in the observational data, we can see this cold blob in the northern Atlantic due to the AMOC transporting less heat into that region.

The climate models don’t show this in the simulations that run up today, they only show it in the future — so the models are kind of lagging behind.

BT: How long have we been aware of these indicators of a potential collapse? Did it only really come into view after the IPCC report was released? Or has it always been there and we hadn’t collated the research yet?

SR: The general concern that there is a risk of AMOC collapse goes back more than half a century. The fact that the AMOC has a tipping point was first described in a famous study by the American oceanographer Henry Stommel in 1961; he showed that the system was unstable because of a self-amplifying feedback. Using paleoclimatic data, the paleo-oceanographer Wally Broecker warned about the AMOC tipping point and abrupt climate changes in a 1987 Nature article titled “Unpleasant surprises in the greenhouse?”

It’s been known for a long time, but until recently it was considered as low probability but high impact. It’s like telling someone who boards a plane that it has a 5% probability of it crashing.

Yet now, in light of new evidence, I think many of my colleagues, including myself, don’t really consider it low probability anymore. That was the reason why we wrote this letter.

BT: So what would climates around the North Atlantic look like if AMOC were to collapse? What regions would be the worst affected?

SR: There would be many impacts. The most immediate one that people probably already know about is the cooling around the northern Atlantic, which is already there in the form of the cold blob. It’s also in the air temperature around that region, it’s the only part of the world that has not warmed, but has been getting colder, in the last 100 years.

So we already have the symptom there, but when the AMOC really gets much weaker still and collapses, then the cold blob would expand and cover land areas as well — like Ireland, Scotland, Scandinavia, Iceland, they would likely get several degrees colder and also drier.

That would then enhance the temperature contrast across Europe, because Southern Europe would still be warm and Northern Europe would be cool. These temperature differences drive extreme weather events, bringing a lot more variability and storms. The sea level would also rise by up to half a meter [1.6 feet] in the northern Atlantic in addition to the global average rise that is happening anyway.

There would also be an effect on ocean carbon dioxide uptake. Currently, the ocean takes up 25% of our CO2 emissions just by gas exchange at the sea surface. The ocean can do that because a lot of that CO2 is then transported to the deep ocean by the AMOC. If the overturning circulation stops, that CO2 will stay near the surface and quickly equilibrate with the atmosphere. That would make it [C02 concentrations] rise faster in the atmosphere.

The AMOC also transports oxygen into the deep ocean. This is also bad news [if this process stops], because if you get an oxygen-depleted ocean it would disrupt the entire web of life in the northern Atlantic, and that would disrupt fisheries.

BT: That paints a very strange picture of our future climate — things being colder around the northern Atlantic, warmer to the south, and there being a lot more CO2 in the atmosphere. What impacts will that combination have globally?

SR: We’d see the whole Northern Hemisphere cool compared to what it would be with just global warming [acting alone]. Although it wouldn’t exactly cool [outright], climate change would counteract that effect in most places, except around the North Atlantic.

In the Southern Hemisphere, greenhouse warming would get worse. There would be a shift in the tropical rainfall belts. We know from paleoclimate records that these Heinrich events, for example, have caused major drought problems in parts around the tropics and in other areas. You would also get flooding from tropical rainfalls shifting to places where people and infrastructure are not used to it.

In terms of more detail, there are surprisingly few studies on that so far. We mostly know from paleoclimate data how drastic and worldwide these changes are, even reaching as far as New Zealand, which is as removed from the North Atlantic as you can possibly get.

BT: What would the impacts be along the East Coast of the U.S.?

SR: There have been discussions about whether East Coast storms would be enhanced by an AMOC slowdown, but I don’t think we’ve reached consensus or that the science is certain. We can see from the past that the effects would be very serious.

But we’re in a bad situation with the general public in that we can’t say exactly what they will be. We can’t just make things up, and we don’t have enough studies that have looked into them.

BT: AMOC’s potential collapse isn’t the only tipping point that we are getting closer to or have even crossed already — tipping points have been crossed for many coral reefs to start dying, and the Amazon rainforest could already be on a path to transform into savanna. How does the AMOC tie into this? Could it start a domino effect?

SR: Let me first say that as an oceanographer, the coral reefs are very depressing. It’s one of those tipping points that has long been predicted, and now we have reached it. That already has an impact because many millions of people depend on them for their food. That’s just a good example of where the warnings by scientists were not taken seriously enough — they warned of this tipping point, and now it’s here.

In terms of a potential cascade, it’s at the forefront of research projects into tipping points to study how they interact with each other. A collapse of the AMOC could enhance the risk of ice sheet instability in Antarctica, or passing the tipping point of the Greenland ice sheet would lead to more freshwater release from Greenland into the North Atlantic that could trigger the AMOC to tip. These interactions are being studied at the moment by several research groups.

BT: The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has estimated that an AMOC collapse would cut the amount of land available worldwide for growing wheat and maize — crops that supply two-fifths of global calories — by more than half. Are you aware of any research efforts being made to estimate the deaths an AMOC shutdown could cause?

SR: No, I’m not aware of that. I think we definitely need it, and it’s one thing we asked for in our open letter: more detailed research on the impacts.

You mention agriculture. In fact, there’s one study of a quite serious reduction expected in the United Kingdom that we cite in that letter, but otherwise there isn’t very much research.

BT: If a shutdown does happen, how long would it last? And how much time would we get to adapt to it?

SR: Well, from past experience, the physics, and the modeling, it would last on the order of 1,000 years until it recovers. So it most likely won’t stay off forever, but on a human timescale, it will be for many, many generations.

One thing that is not so widely appreciated, I think, is that if AMOC were to recover one day from a long period of collapse, its recovery would, at first, be an even worse disaster than the collapse. That’s because the recovery happens much faster than the collapse. The AMOC would ramp down over a period of 50 to 100 years until it ceases, but its recovery — the sudden springing up of deep ocean convection — would happen within one winter. That means it would get much warmer in the North Atlantic within 10 years or less.

BT: Could we have crossed the tipping point already? And if it were passed, at what point would we know for sure?

SR: It actually isn’t really easy to know that for sure. What the tipping point means is that from now on, there is self-amplifying feedback that will make the AMOC slowly die, over decades to 100 years. But there wouldn’t be any drastic sign that you can measure when you go out there on a ship or look at it from a satellite, so you wouldn’t be sure.

You would see, of course, that the AMOC is weakening, and it already is, but you wouldn’t know if it is now already doomed or if it could recover if we stop global warming.

BT: I’m sure the answer for this one is obvious, but what should politicians be doing to stop it?

SR: The main thing is to prioritize sticking to what was agreed in the Paris Agreement. Namely, to limit global warming to 1.5 C [2.7 F], if possible, but certainly well below 2 C [3.6 F].

The “well below” part often gets forgotten. That means 1.7 C or maybe 1.8 C. If we manage to do that, and all countries have committed to do that, then we can really minimize the risk of going over the tipping point. No guarantee, but I think it’s very likely that we would actually avoid going across that tipping point if we stuck to the Paris Agreement.

RELATED STORIES

—Gulf Stream’s fate to be decided by climate ‘tug-of-war’

BT: You’ve spoken about the need for better research into AMOC. What should scientists be doing to better understand and forecast a potential collapse?

SR: Just a while ago, Britain launched a moonshot project costing £81m [$105 m] to build an early warning system in the northern Atlantic. So that’s one thing: at least monitoring it better. Maybe we won’t get a reliable early warning, but at least we have a better chance to see whether we are close to the tipping point or have already crossed it, even if it’s very hard to be sure about that.

The other thing one can do is to build resilience — useful adaptation measures that are good regardless of whether it gets warmer or colder. Britain, for instance, could insulate its houses better. That helps in heat waves as well as in cold weather. But I think to me, the prime concern would be that we really must prevent this from happening. Trillions of dollars are spent every year subsidizing fossil fuels, that just has to end.

BT: I get emails from readers who are worried about this and they sometimes want to know what they should be doing on an individual level too. Do you have any advice?

SR: I think ordinary people can talk to their friends, neighbors and family about climate change. They can also vote — so as long as they live in a democracy, people do have a voice — and make it clear to politicians that they’re only going to vote for them if they take the Paris Agreement very seriously, which many don’t. Unfortunately, that’s why we probably missed the targets, but people can demand that.

If you own a home, you can also install a heat pump, use less fossil fuels, and switch to electric vehicles. There are various options, but I think primarily this is a political issue. Individual action to reduce your own emissions is fine, I do that too, but the prime thing is to get policy change.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Staff Writer

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he’s not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.